The South East Leadership Academy is proud to support Disability History Month as part of our ongoing work to develop compassionate and inclusive leaders and to build supportive and inclusive cultures across the NHS. As part of our collaboration with the South East Equality, Diversity and Inclusion team we have dedicated this page to disability History month. We will be sharing stories, resources and events throughout this month to raise awareness and advance disability equality.

UK Disability History Month

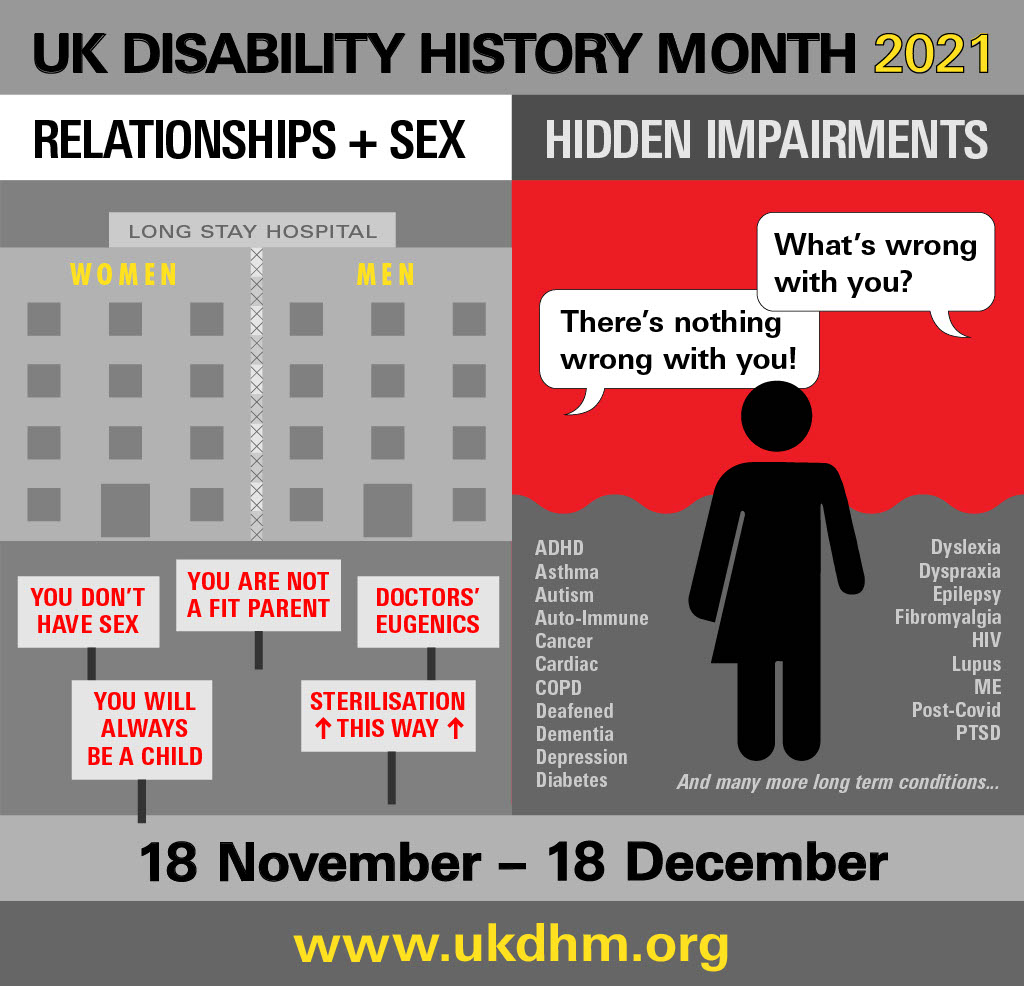

The joint themes in 2021 are:

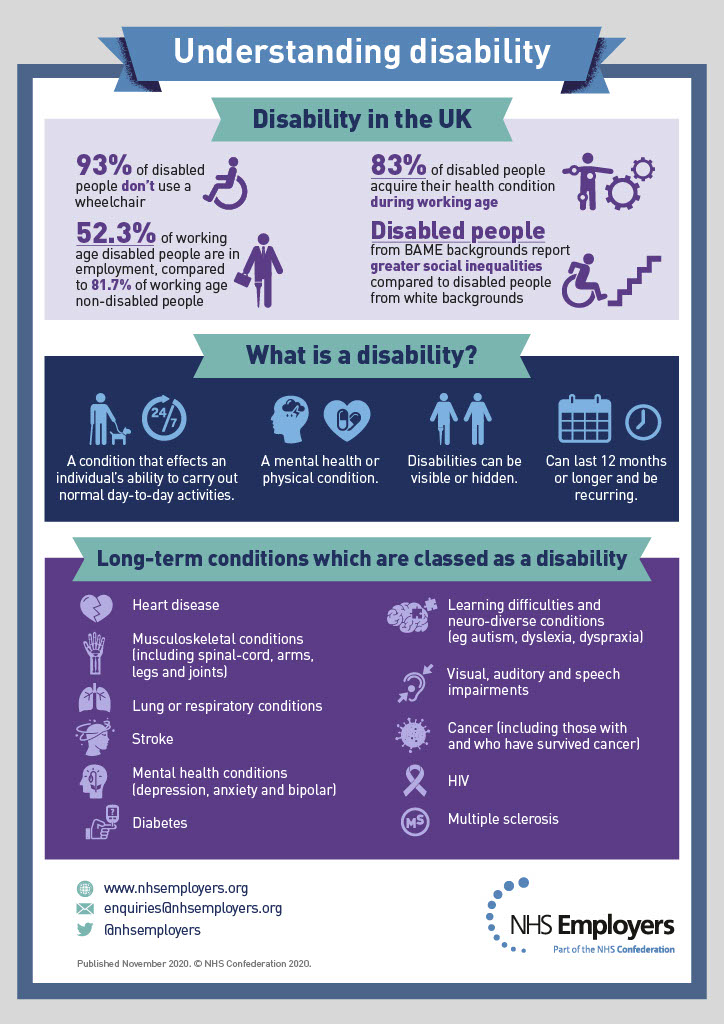

Definitions of disability

The Equality Act 2010 defines disability as “if you have a physical or mental impairment that has a ‘substantial’ and ‘long-term’ negative effect on your ability to do normal daily activities.” (2).

More than half the 13.5 million people currently identified as disabled in the UK have hidden impairments.

Understanding Disability

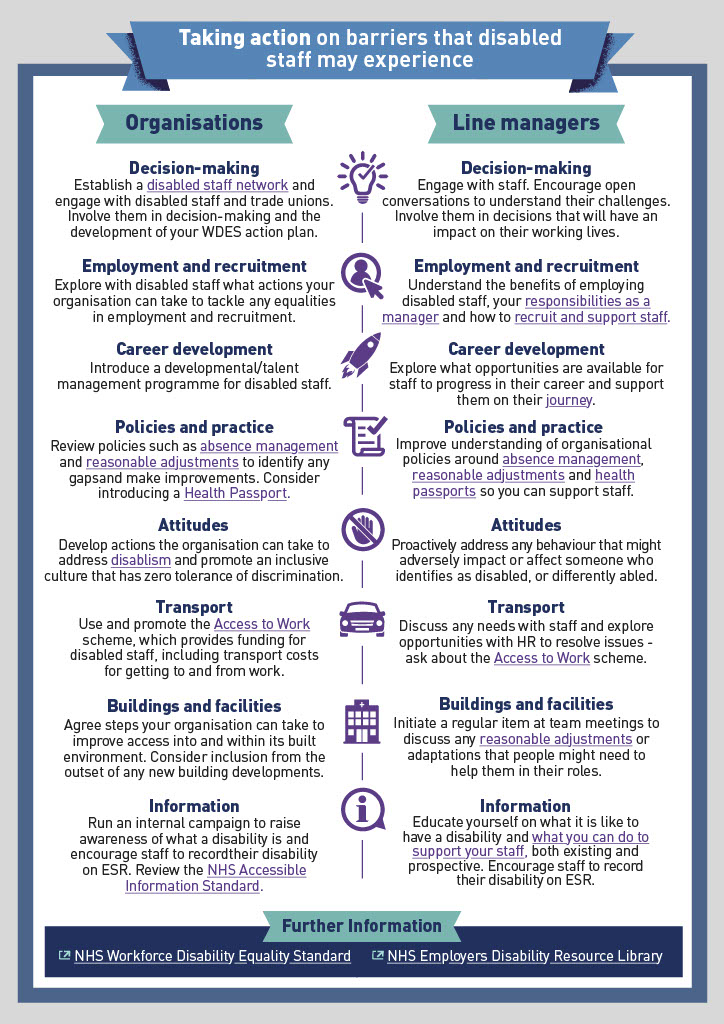

Workforce Disability Equality Standard

The Workforce Disability Equality Standard (WDES) is a set of ten specific measures (metrics) which enables NHS organisations to compare the workplace and career experiences of Disabled and non-disabled staff. NHS organisations use the metrics data to develop and publish an action plan. Year on year comparison enables NHS organisations to demonstrate progress against the indicators of disability equality.

Making a difference for Disabled staff

The WDES is important, because research shows that a motivated, included and valued workforce helps to deliver high quality patient care, increased patient satisfaction and improved patient safety.

The WDES enables NHS organisations to better understand the experiences of their Disabled staff and supports positive change for all existing employees by creating a more inclusive environment for Disabled people working and seeking employment in the NHS.

Disabled workers’ experience during the pandemic

Before the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic disabled workers faced huge barriers getting into and staying in work, including significant difficulties in accessing reasonable adjustments, in spite of the fact that this is a legal duty for employers (3).

The pandemic, and the huge changes it has caused to our everyday lives, has exacerbated the barriers disabled people face. Not only have disabled people been disproportionately affected in terms of loss of life, with six in 10 Covid-19 related deaths being disabled people, but pre-existing workplace barriers have been accentuated by the pandemic (3).

The TUC commissioned in-depth research. In February 2021 we surveyed 2,003 disabled workers, or workers who have a health condition or impairment, or were shielding and who were in work at the start of the pandemic (3). Please see below to read their full report

History of disability:

Key facts in the UK

The Second World War

As the Second World War ended in 1945, public concern shifted to the 300,000 ex-servicemen and women and civilians who had been left disabled by the war.

Rehabilitation for all

The 1944 Disability Employment Act promised sheltered employment reserved occupations and employment quotas for disabled people. Initiatives to restore the fitness, mobility, daily living skills and morale of disabled servicemen and women spread to the rest of the disabled population. The new National Health Service extended rehabilitation services to workers disabled by industrial accidents (4).

World War II had put a high value on physical health and ability, but resulted in a large number of disabled ex servicemen needing support (4). © Wellcome Library, London

Direct action

Disabled people did not remain passive, and many campaigning disability charities formed in the 1940s and 50s. A new social movement was started by a ‘silent reproach’ march of disabled ex-servicemen in 1951(4).

In the 1960s and 70s, the civil rights movement in America inspired disabled groups to take direct action against discrimination, poor access and inequality. A ‘social’ rather than a ‘medical’ model of disability emerged and eventually, in 1995, the Disability Discrimination Act was passed (4).

Inclusion and access

The new social model was concerned with people’s rights as members of society. The question of access was critical. Disabled people needed adaptations made to their environments if they were to be properly included. Separate facilities were built at first, but soon architects and planners took on the idea of ‘universal design’. They created buildings and landscapes which every person could use every part of (4).

The Paralympic Games

Great changes took place in sport. The inspirational refugee neurosurgeon, Ludwig Guttman (1899-1980), was in charge of Stoke Mandeville hospital Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire. Here, patients paralysed in the war began to compete against each other as part of a pioneering rehabilitation method (4).

In 1948 a wheelchair archery competition was held on the lawns of the hospital. In this humble way, the Paralympic Games was born. The Games are now the second biggest sporting event on earth, and many elite disabled athletes have become sporting icons in their own right (4).

The end of the asylum

The era of the asylum finally came to an end after a series of scandals revealed neglect and abuse. In 1981 the Jay Report promoted a care in the community programme for people with learning disabilities and mental health needs. Tens of thousands of people left the long-term hospitals and returned to mainstream communities (4).

The Victorian ideal of a safe institutional ‘asylum’ has been replaced by new visions of equality, inclusion and universal access. Their long-term impact will be seen in time (4).